Howlin' Wolf

Smokestack Lightning

The Complete Chess Masters 1951-1960

Universal

"He sang with his damn soul. He knew he had something to say."*

Ladies and gentlemen, this is where it all started.

One of the more annoying trends in recent years has been the misappropriation of the term R ‘n’ B to describe soft, largely American, pop music. At the current time the official R ‘n’ B chart is dominated by recordings by Whitney Houston and Rihanna, Beyonce and JLS, and it’s just not right. R ‘n’ B is the music that influenced the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, Dr Feelgood and a host of other important bands of the sixties and seventies. When the Who advertised their shows as offering ‘Maximum R ‘n’ B’ it meant they were wild and rocking. Make no mistake, the real rhythm and blues is the music of the electric bluesmen who turned the world on its head, artists such as BB King, Muddy Waters and, the best of them all, Howlin’ Wolf.

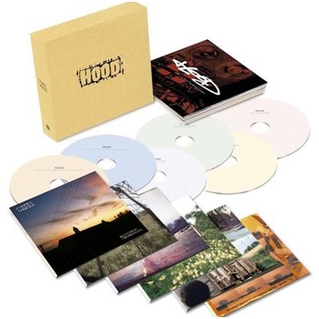

There have been numerous box set releases from all of these artists over the years, but at the end of 2011, another limited edition hit the shops, a nicely produced set featuring all of the recordings laid down by Wolf for the Chess label between 1951 and 1960. Packaged in a neat book format, the four discs offer ninety-seven tracks, including many rare alternative takes, all remastered by top engineer Erick Labson, who now has nearly a thousand remastering credits to his name. Labson has done his job well; the remastering has not detracted from time and place and has enhanced rather than smoothed out the sheer rawness of some these songs. And the set brilliantly captures the transformation of Wolf from the roughest of the all the bluesmen into one of the most potent rhythm and blues artists of all time. Poignancy was added to the release with the recent death of Wolf’s impossibly influential guitarist, Hubert Sumlin, so what better time to reassess the work of one of the world’s greats?

For those more familiar with Wolf’s incredible recordings of the late fifties and early sixties, some of his early history may come as a surprise. Chester Arthur Burnett had impeccable blues credentials. Born in Mississippi around 1910, he was taught guitar and how to perform by the legendary Charley Patton, learned the harmonica with Rice Miller, and regularly played with such luminaries as Floyd Jones, Robert Johnson and Son House. His outfit were one of the rawest blues bands in town and earned themselves a mean live reputation. It was a combination of this and the Wolf’s broadcasts on local radio that led to him being recommended to Sam Phillips, later the founder of the world famous Sun Records. At the time Phillips ran the Memphis Recording Service where he recorded tracks at his own Sun Studio and licensed them to established labels who were geared up for promotion and sales. Phillips sent out Wolf’s tracks for release on Chicago’s Chess label, though in those early days he did not record exclusively for them. This box set, then, is not a comprehensive collection of the bluesman’s works, but exactly what it states, a collection of all the Chess masters. With Phillips and Chess eventually falling out, ostensibly over Phillips’ desire to start up his own label, Burnett was persuaded to pack his bags for Chicago and record exclusively for the northern label, and he lived in that city for the remainder of his life.

The loss of Burnett was a terrible blow for Phillips. When he first met the singer he had appeared both imposing and reticent, but when the 41-year-old appeared in his studios to lay down some sample numbers, Phillips was blown away. So in awe was he of what he was hearing, he felt unable to contribute in his usual way to aid the recordings. For the rest of his life Burnett was the one. Despite going on to launch the recording careers of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and Jerry Lee Lewis, all singers he admired greatly, Phillips could never hide his disappointment at having lost Burnett and was convinced he would have made the singer into a huge, national star. Talking of his performances, Phillips commented, “This is where the soul of man never dies.” Howlin’ Wolf was the real deal.

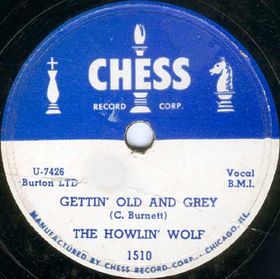

Thirty-six tracks in this collection were recorded at Memphis before the move north, and they are as raw as you like. Mostly self-penned, they are dominated by Burnett’s incredible voice, timing and intonation, as well as the prowess of guitarist Willie Johnson. Johnson could play like an angel, as witnessed on ‘Howlin’ Wolf Boogie’ (pure rock ‘n’ roll from 1951!), ‘Look-a-There Baby’, ‘Streamline Woman’ and ‘My Last Affair’, but he could also produce the dirtiest guitar sound you have ever heard, sending out blasts of distortion, and if you are a fan of independent music, look no further as to where it all began. ‘Gettin’ Old And Grey’ is immense, with Johnson at his sparkling and screaming best, and the bluesier the song, the more pain Johnson squeezes from his instrument.

The move to Chicago marks a major change in sound; the recordings are more professionally made and arranged, sounding less raw, but if anything the greater clarity serving to enhance the power and uniqueness of Burnett’s voice. The first track laid down, ‘No Place To Go (You Gonna Wreck My Life)’ is simply huge, the vocals ripping through the music as it echoes the relentless trudge of everyday life while, from the same session, Otis Spann’s piano lifts ‘I’m The Wolf’ to the heavens. Not only did the better Chicago facilities improve the Wolf’s sound, but two other factors made this move vitally important for Burnett’s musical development. When he first went into the studio, Wolf was introduced to bassist Willie Dixon who later went on to write the greatest of his songs, and soon after his arrival, the singer invited young guitarist Sumlin to join him up north. The rest, as they say, is history.

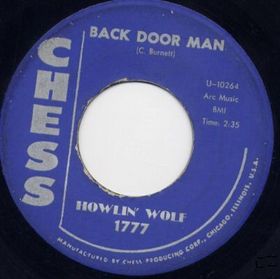

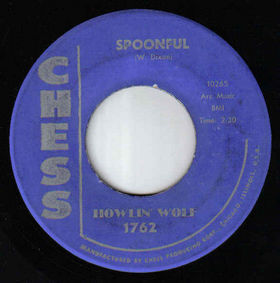

While Johnson still joined his former boss on occasion, it was the almost omnipresent Sumlin and Dixon who were gradually to move the Wolf in new directions. It was slow process, but Dixon served notice of his songwriting abilities in 1954 with the incredible ‘Evil (Is Goin’ On)’ and under their influence Burnett’s own songwriting increasingly began to show a wider musical sensibility. This was to bear fruit in a major way with 1956’s famous ‘Smokestack Lightning’ and ‘I Asked For Water (She Gave Me Gasoline)’, but Burnett also showed he was still able to produce raw blues classics such as the brutal ‘I’ll Be Around’. It’s fascinating to listen the sound developing, and by the end of the final disc, in June 1960, Wolf is completely in the hands of Dixon and Sumlin, as we are left with three Dixon songs, ‘Wang-Dang-Doodle’, ‘Back Door Man’ – which was covered by the Doors on their debut album – and what must be one of the greatest blueprints in musical history, the untouchable ‘Spoonful’ with its gorgeous guitar work, Dixon’s rumbling bass and Wolf’s impeccable delivery. It really doesn’t come any better than this.

Retailing just over thirty quid, this is a nice package and one of the best history lessons you will ever have. If you really want to know where it all started, it’s worth every penny.

* Sam Phillips, as recorded in a forthcoming biography by Peter Guralnick

Hood

Re-Collected

Domino

Released 20th February 2012

"Blues is easy to play, but hard to feel."*

There's little doubt that Hood have the feeling.

For some, the blues will always be twelve bars and a harp, an outlet for the oppressed giving voice to their pain with a force and beauty that left its imprint on the consciousness of the world. But days change and humanity endures; pain is universal and pressure tells. And loss. And despair. Whether in the Mississippi Delta or the blurred fringes of post-industrial England, our lives are bound to our environment, inextricably linked by roots that run deeper than our understanding and here we grind out our lives. Wolf knew the blues were not just about race, or time, or place. They were about the feeling. Few modern bands capture that feeling. And none sing the blues like Hood.

Formed in the early nineties by brothers Chris and Richard Adams, the band’s story proper begins in 1997 when Domino records signed them up and they set to work with Matt Elliott (the Third Eye Foundation) recording their third album proper, Rustic Houses, Forlorn Valleys. Here the band abandoned the short, experimental tracks that had filled their earlier releases and replaced then with beautifully shaped, maudlin epics that bordered on eight minutes apiece. They went on to record four albums for Domino; together they featured six fewer tracks than had graced their first two releases.

Their timing was perfect. The giddy optimism of Britpop was dying away, the celebratory turning to introspection, and that was second nature to these Yorkshiremen. While euphoria is transitory, life can be long, and Hood understood the need for space. They were well named; the band absorbed every nuance of their West Riding environment: declining, often dangerous, industrial cities groping for regeneration and a new purpose, and a fringe of rural pastures, beautiful in themselves, but uneasy in the shadows. Hood stood helplessly in between, needing the air to breathe but terrified of the emptiness; always at home, but never at home.

In Hood releases there is no time, it is always Autumn and always will be. 1998’s Rustic Houses, Forlorn Valleys reflects that enormity. Its six tracks are so painstakingly built you hardly realise they have become walls, trapping you in a landscape where it always rains and the only emotion is despair. It’s delicately done. It may be thirty seconds before the next note arrives, but it is perfectly placed, creating an all-embracing vision, and it is the voices that alienate, half spoken, half sung, and utterly lost. “Cinematic, silent skies. Resident, silent. Forget the dreams you had.” Here nothing is changing; this is forever. And there is a lot of emptiness in forever, once the feeling is lost. Amongst the gloom ‘Your Ambient Voice’ is immense, a lone guitar insistently embarking on a journey to nowhere, ignoring whatever is thrown in its path in its frightening monomania. “Do you know what it is like to regret everything? I regret everything.” If this isn’t the blues, God knows what is.

1999’s The Cycle Of Days And Seasons, its cover featuring a single leaf on bare branches, walks on similar terrain though it treads a little more lightly, the band content to capture a snapshot of eternity rather than build the whole of it piece by piece.The mood is less desperate, empty despair replaced by mere overwhelming sadness and bewilderment. Musically it is less homogeneous, introducing dub effects and more sampled noises, though there are some lovely guitar parts and carefully strewn drum breaks that carry the pieces along, giving a renewed vigour to faltering steps. The image of the church, a potent symbol of the cycle of life and death, is everywhere. The album opens with organs to which we later return, while ‘September Brings The Autumn Dawn’ is played out over a whispered prayer as the bells toll their lament to another dying year. Yet this is not enough to offer redemption, ‘Roads Lead Northwards’ declaring, “I wanted to steal your soul so you couldn’t sleep. I haven’t slept soundly for years.” Days change, but they don’t bring peace.

Ostensibly, this Re-collected box set was compiled to mark the tenth anniversary of Hood’s critically acclaimed 2001 album Cold House. Though the musical focus continued to shift, to say this was a sea-change in approach is wide of the mark. Following in the path of its predecessor, this album looks inwards, dwelling on loss and the pain of dying relationships. The cover, featuring a blurred image of the countryside, is telling in that there is less focus on place and more on self and where before the music was carefully pieced together around you, here it is equally carefully deconstructed, leaving you detached and alone. Lines of songs are not sung, but each individual word is stressed in isolation. This is alienation, and the influences of dub, drum and bass and the deliberately obscure contributions of American MCs Doseone and Why? only add to the dislocation. ‘This Is What We Do To Sell Out(s)’ is mixed to pieces, while the dirge of ‘Branches Bare’ proclaims, “We spit in the pond to give the fish something to pray to. Sometimes the sunset doesn’t want to be photographed.” There is no connection, anywhere. If there is happiness it is in the past meaning even time, relentless in its cycles, is now an enemy and time is all that is left before you die and the memories are lost. God, this is sad stuff. A cold house indeed, both an empty home and musical influences drawn in to separate rather than bind.

It was to be four years before Hood’s next album was released, but their progress in the intervening years can be traced on the EPs Collected disc here which features their five Domino EPs, three of which fill the gap between the band’s final two albums. You Show No Emotion At All (2002) shows a growing confidence with conformity while The Lost You (2004) demonstrates a real pop sensibility: ‘You Can’t Breathe Memories’ is a delicious, harmonic dreamscape and the angular ‘The Rest Of Us Still Care’ is simply gorgeous, losing itself in the heavens midway through before plummeting back to earth. Guitars dominate again in 2005’s The Negatives, ‘The Fact That You Failed’ building from a slow dubby opening into a fiery guitar salvo.

So, if Hood had not found redemption in the intervening years, by the time Outside Closer was delivered in 2005, they had at least given a new voice to their pain. Following a brief, shimmering introduction, ‘The Negatives’ is a straightforward pop tune and leads to one surprise after another. ‘Any Hopeful Thoughts Arise’ is beautiful, slow building, melancholia laced with the saddest of strings. “These could be the last words I ever say to you. There is a space between me and you,” is the lament; Hood are still singing the blues. ‘End Of One Train Working’ is a solemn, empty march while ‘Winter 72’ is an effects-laden ballad that successfully wends its way through a post-punk storm of guitars, glorious as it is surprising. And all the time there are clues that this is the final say, that Hood can add little more. The titles of the final tracks, ‘Closure’ and ‘This Is It For Ever’ hint at the end, the former a gorgeous, slow paced ballad, dripping remorse, and the latter crying unformed before crawling away to die. Hood have not recorded since.

The Hood Tapes is the sixth disc on offer here (there is also a booklet with comments from many of the contributors, fans and critics) and offers the only tracks you could not get hold of easily from other sources. It lacks the coherence and background of the albums, but has its moments of quality. The question is whether it is worth buying this set for a handful of new Hood moments. It’s a nice thing, and limited to five hundred sets, but it is not cheap and as numbers have dwindled, the price appears to be rising: it is now commonly being offered at around sixty quid. If you don’t know the band or their music, and have a mind to explore new territory, give it a go. There really isn’t anything else quite like it. But don’t expect to come out laughing.

* Jimi Hendrix