In the 1980s 4AD was more of a religion than a record label, the quality of the work it produced in that decade remaining unsurpassed. Adam looks at Martin Aston's new book on the label's glory years.

The rise of the independent music label following the punk revolution of the late nineteen-seventies is one of the most important developments in our recent social history, giving whole generations a sense of belonging, ownership and pride. Whilst the kids of the twenty-first century have scores of other things in which to invest their time and emotions, back then there was only football, music and sex. And for many of us music was the first and the last of these; nothing else could set your soul alight and send your spirit soaring through the heavens. The shallow kids listened to what was in the charts and went to parties, those of us who shied away from such a hollow existence went underground and shunned the light. And that action defined us and our outlook on life; a generation detached. A generation demanding something better, a more thoughtful stimulation; something new, envigorating and cutting. And hundreds of like-minded musicians helped provide it, along with the labels that opened the doors for them and the journalists who wrote about them. Of course music could be enjoyed from a whole variety of labels, but there always tended to be one that mattered more than the rest. For some it was Manchester's Factory of which much has been written over the years, for others the cute pop of The Subway Organization struck a chord in lifestyle and outlook, while for those who found beauty in the shadows Ivo Watts-Russell's 4AD became their second home.

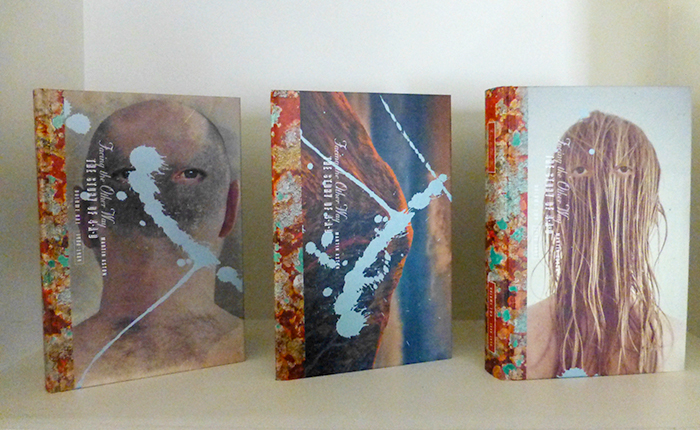

Most of the successful indie labels manufactured an indentity for themselves through the type of music they released and the style of the artwork they produced, but 4AD took this to a whole new level, infusing all they did with quality and artistry, treating the music with the importance we all knew it deserved. 4AD understood and for a decade and more they were giants in the field, releasing a dazzling series of records the like of which the world had never seen; transcending everything a record label was supposed to be. Of course we knew deep down it would all end in tears, and so it did, but the intimate details of the story have never fully been revealed. Many websites have paraded their love for the label but finally all the facts have been captured in a book by music journalist Martin Aston, Facing The Other Way - The Story of 4AD, which has been published by the Friday Project (who have recently brought us Throwing Muses' Purgatory/Paradise book) in both standard hardback format and in a limited two-volume set, signed by Aston and designer Vaughan Oliver, with accompanying CDs housed in a separate booklet. One volume and disc cover the 1980s, with the others covering the 1990s; the story only being taken to the end of the millennium when Watts-Russell sold up and buried himself in the silence of an American desert.

Given the nature of the subject it would have been easy for Aston to lose himself in a sea of overblown rhetoric but fortunately he writes unpretentiously and easily. The main aberration is that he abandons the traditional British use of a collective noun as a plural in favour of the fussier American approach and this jars at every reading, even causing confusion to the author who lets slip the appalling "Lush was always insecure about their abilities". You can't have it both ways. As clearly no Britons would talk in this manner, he has also amended his quotations to fit in with this stylistic approach which immediately raises the question of when is a quote not a quote? Any alteration surely must raise doubts as to authenticity and accuracy, and if it is appropriate to adjust a quotation why not amend some of the grating split infinitives contained therein? Aston also forgets on occasion that a person is who and not that.

Grammar aside, Aston's desire not to intrude on the narrative makes this book very much a story (as its title claims) and not a critique. On the odd occasion he takes the plunge to air his views on a record he proves to be perceptive and knowledgeable, though on the whole he is placid enough to accept the views of Watts-Russell or the artists involved on a particular recording, occasionally working to reinforce their opinions. This all helps to aid the flow of the book which is rarely confrontational and his style is well suited to deal with the passages when the memories of the protagonists are in conflict, his moderate stance helping to guide the reader along the most logical path. Yet musicians, producers and impresarios rarely have unblinkered views of their work and should not be let off so lightly, especially when important recordings are dismissed and moderate ones praised.

More puzzling is Aston's embracing of the bands the label signed in the 1990s. He paints a telling picture of Watts-Russell's decline into mental illness which leads to his move to LA in 1993 and consequent dislocation from the label he has shaped. The despair felt in 4AD's London office at this apparent betrayal is portrayed only too well, with the label's founder rejecting all of the prospective signings suggested to him from across the Atlantic, clearly underlining his inability to function as a label boss by admitting that "music would scare me by releasing too many emotions". Consequently 4AD's output from this date mirrored this failing, drifting more and more into the suffocating swamps of soulless Americana and with emphasis being placed on the technical rather than the visceral; music that lacked the spark or vitaility to get your heart pounding and spirit soaring. The greatest record label on earth began to embrace the values of prog and the west coast and it was horrible to behold. 4AD may have stumbled awkwardly into the nineties but after ninety-four it slowly drowned in Watts-Russell's emotional malaise. That Aston sees releases by Tarnation and Liquorice in 1995 as raising the game is bewildering, but describing The Paladins' 1996 abomination of an album as a "scorcher" is pretty much inexcusable. It is a record that will always stand out as one of the most important in the history of the label as it was the moment we all knew 4AD had died. Despised by the label's employees in London, this one record wiped away virtually all the remaining goodwill that still existed between 4AD and those who had supported it fanatically since its early days. Watts-Russell describes it as "amongst the most pure and satisfying projects that I ever worked on"; those of us who bought it because it was on 4AD felt the complete opposite. Despite odd moments of brilliance from Throwing Muses and Tanya Donelly, the remainder of 4AD's catalogue from that moment until Watts-Russell's departure in 1999 read as long forgotten words in a tired obituary.

For, if 4AD stood for anything, it was the spark. One of the genuinely innovative independents to spring up in the wake of punk it embraced the post punk ethos of pushing boundaries, pleasingly in both music and design, through deconstruction, through daring, and through sheer inspiration. Watts-Russell could spot potential in the most unlikely arenas and identify exactly the musicians who could both feed from and add to his overall vision for the label. His largely hands-off approach in the studio gave bands the time and space to grow naturally and while there was no unifying 4AD 'sound' (though many would claim the opposite), there was certainly a unifying 4AD 'feel', underscored by the stunning artwork of Vaughan Oliver and Nigel Grierson's 23 Envelope. And at its heart was the understanding that the artefact you bought at the record shop was infused with quality at every level; that a frisson of excitement would run through you as you took the disc out of its cover; that your heart was about to take another pounding.

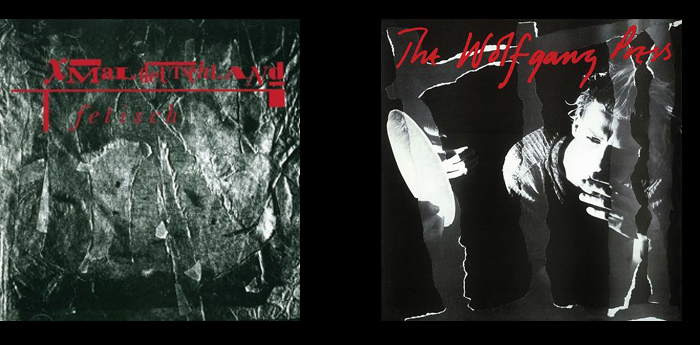

From its very beginnings 4AD had bite. Whether the searing feedback of Rema-Rema, the sneering disdain of Bauhaus, the hollow laughter of Mass, the angular scything of In Camera or the terrifying, psychotic howl of The Birthday Party there was an astonishing power to the music it brought to the world. Having found its feet by 1982, both in terms of sound and vision, the following year it produced the most perfect series of releases anybody could dream of. Watts-Russell may name 1988 as the label's zenith, but how can anything compare to The Bad Seed, Fetisch, 'Breakdown', The Burden of Mules, 'Song To The Siren', Sunburst and Snowblind, Head Over Heels and Colourbox? It was an absolutely staggering collection of records and every one was dressed to kill. How could you help but fall in love with such a label? How could you not thrill to Nick Cave's perverse enjoyment of death and decay in 'Deep In The Woods', Anja Huwe's screaming orgasm in 'Stummes Kind' and Manuela Rickers' chopping guitars in 'Boomerang'? How could your heart not clatter along to the pounding rhythm as Colourbox fell off the edge in 'Breakdown' or shudder at Michael Allen's primal wail in 'The Burden Of Mules'? Even the quieter moments had the power to move the world. Elizabeth Fraser could melt your insides with a single line whether in the sweet caress of 'Sugar Hiccup' or the deadly call of 'Song To The Siren'. Power, majesty, grandeur, taste ..... 4AD had it all. And still to come were the classical shades of Dead Can Dance, the grubby howls of Pixies, the addictive rumblings of The Breeders, the intricate mantraps of Belly, the gentle guitar showers of Pale Saints, the spiky poptones of Lush and the soul shattering confusion of Throwing Muses, unparalleled in its harrowing, riven beauty.

That this roster should be reduced to His Name Is Alive, Air Miami, Liquorice, Heidi Berry, Lisa Germano, GusGus, Tarnation, Mojave 3 and Cuba before Watts-Russell threw in the towel is enough to reduce you to tears. And probably did. On more than one occasion. There was nothing there to ignite the spark in your soul and little beauty beyond that some find in maudlin self-pity. The one attempt to try and recapture the label's backbone by the signing of Scheer is here treated as an aberration rather than the first step on the obvious road to recovery. It lifted the label's staff in London and gave hope to its followers that it was not all going to be a downhill slide, but sadly it was the last such positive gesture. There was no way back. And after Watts-Russell's departure, 4AD continued to tread on the shadow of nowhere; today it is just another label releasing the occasional decent record and means nothing more than some very magical memories. But it leaves you asking what could 4AD have been now had it not lost its way in the nineties? What could it have done with Cranes, Curve, See See Rider, Catherine Wheel, Gallon Drunk, Drugstore, Crime & The City Solution, Faith Over Reason, Sigur Rós? It could have ruled the world rather than die choking on its own vomit.

For obvious reasons, the tome on the nineties fails to entrance as much as its predecessor as the minutiae on largely average records is not particularly enthralling. And as Watts-Russell's mental heath spirals in a downwards loop, his plight attracts very little sympathy as everything he has built falls apart, impacting on his employee's lives and careers. No doubt his very British avoidance of discussing his personal problems is met by the equally British feeling that he should have pulled himself together. The towering figure in the sorry tale turns out to be Vaughan Oliver whose astonishing work went a long way to holding together a fragmenting label, showing the sheer power imagery can have over the imagination. Oliver is entertaining thoughout; a party animal with a powerful work ethic and an obsession with photographing his genitals. He is one of the few protagonists to emerge with much credit; anyone who has worked with bands can understand the damaging effects egos have on maintaining harmonious relationships and though 4AD made efforts to treat their artists as respectfully as possible, it would have been miraculous had there been no discord.

The Cocteau Twins' Robin Guthrie comes in for the biggest pounding and in turn emerges as the severest critic of the label's performance. He makes a fair point over his feelings that he was undervalued and the constant comment that Watts-Russell was no businessman holds little water as he was the man in charge and should have fought for understanding. However, Guthrie's constant failure to give proper voice to his concerns undermines his grievances and the fact he was a belligerant drug addict also doesn't help his case. His criticisms over the artwork for Cocteau Twins' records do resonate, however, as one of the label's most important bands were matched with some of its least inspiring artwork, the efforts for 'Love's Easy Tears' and Victorialand being particularly disappointing.

Indeed, those artists who did not buy in to the 4AD 'feel' come out worse. AR Kane, the streetwise Londoners, felt no affinity with the label's seemingly middle class pretentions and had no problems in fighting their own personal corners in any conflict; Watts-Russell's indifference to them is obvious despite the duo contributing to the label's biggest ever success. The Birthday Party are frowned upon for wanting to provide their own artwork and come across as perennial outsiders, while The Wolfgang Press and Dead Can Dance are also criticised for not falling under Vaughan Oliver's spell. In truth, Dead Can Dance's record covers improved immeasurably when they finally caved in with A Passage In Time; their own artwork for the Garden Of The Arcane Delights EP had been especially horrendous and Watts-Russell had blankly refused their offering for Aion. Watts-Russell's treatment of some bands who he encouraged and then set aside also paints a grey picture of the man while Aston outlines a fair degree of internal bickering, jealousy and plenty of 'he said, she saids' as the tale unfolds.

Yet he also neatly portrays the more positive side of the label: 4AD's initial indifference to the amount of records it sold, the refusal to play the game, the supporting of bands who had yet to fulfil their potential, the camaraderie that existed between both bands and staff, and the vision that worked as a unifying force between the label and its many adherents. And virtually all of this was down to Watts-Russell and his unique perspective on what a record label should be. Make no mistake, 4AD was not like any other label before or since; it represents the high water mark of independent music and Aston's cataloguing of its first two decades over 617 pages is a fitting tribute, neither too long and complex nor too short and ephemeral. You may not agree with all he says but applause is due merely for managing to talk to some of the music world's most elusive individuals.

As well as the limited edition deluxe package, designed by Vaughan Oliver, the standard hardback is retailing for around sixteen quid at the current time or can be borrowed from the library. The two CDs included, one covering each decade (twenty-two tracks on the first, twenty on the second), can also be purchased as mp3s for around £7.50 for each collection. What joy it must have been to have had the opportunity to pick out these tracks though there is no clue as to whose choices they are (presumably Aston's). Five or six from the eighties would have made it on to our chosen collection, and perhaps one from the nineties, but 4AD meant different things to different people and there are unsurpassed archives in which to delve. If you love the label, you will love the book; if you don't know of 4AD then start listening now and read the book as you go. There are incredible treasures to uncover and we envy anybody discovering them for the first time.